Conservation

The preservation and conservation of seals is extremely important, especially since impressions can easily be lost through accidental damage or careless handling. Therefore SIGILLVM invites professionals in this field to join the network and to bring their experience into exchange with others interested in seals.

Conditions for Conservation of Sealed Documents

Alterations and Conservation of Wax Seals

Generally the climatic conditions for the conservation of graphic documents equally apply to wax seals and bulls as long as the absence of atmospheric pollution is secured.

It is important that the conditions of conservation remain stable, in particular for the hygrometry, as the materials are extremely sensible to changes in humidity. A level of humidity that is too high may cause severe alterations such as mould, corrosion or hydrolysis. Considering that too low temperatures raise the environmental humidity, called in conservation relative humidity; however, a too warm place could provoke a desiccation of the parchment while the textiles are threatened by deformation, breakage, and disruption.

With wax seals, the loss of fatty acids and non-permanent alcohols causes saponification, so the material becomes both opaque and friable. Such organic materials are vulnerable against attacks of insects and microorganisms, which often become apparent through holes or mould.

The major principle of conservation is to handle the objects with greatest care. Most damages in collections are of mechanic character: cracks, missing pieces or pollution. Such damage is caused by poorly executed handling and inadequate organisation. It is recommended to arrange the objects individually, well-supported and free from dust. The fragile objects must not be touched or stored on top of each other.

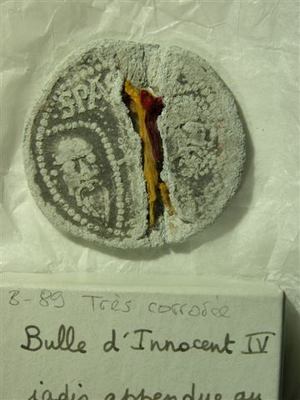

Alterations and Conservation of Metals

Although alterations in physical or chemical categories are rather rare, one can observe corrosions of the metals, discolorations or desiccation of organic materials. Metals, both that of bronze matrices and lead bulls, are extremely sensitive against humidity and volatile pollutants. They have to be stored in an absolutely dry environment. No traces of acid gas or sulphur (not even wool, carpet, etc.) should be found together with the object. Moreover, pieces of wood containing acid or glue (principally oak, plywood, chipboard), but also boxes and papers containing acid have to be removed.

Forms of active corrosion are easily identifiable. An altered metal presents with indentations, deformation, changes of colour and the loss of material in the form of matte powder. For those objects made of copper alloy, such as the bronze matrices (this is an alloy of copper and tin) one can observe green surfaces which derive from the acetates of copper. They remain from the corrosion of copper that is generally named ‘green rust’. On leaden objects the corrosion appears white and this specific carbonate of lead is commonly called ‘white lead’. Finally metals containing iron show grey or red areas known as rust. Metallic sigillographic objects should only be handled when wearing gloves, preferentially of nitrile rubber, because humidity and perspiration is enough to cause active corrosion (gloves made of latex are unsuitable as they contain powder that affects certain metals). In order to react quickly to degradation, it is important to check the condition of collections regularly.

Materials on Conservation

4th international Round Table of seal conservators

On the 4 June 2016, our SIGILLVM Board Members Agnès Prévost and Marie-Adélaïde Nielen from the National Archives in Paris, convened a round-table meeting of seal conservators to discuss current issues on the preservation and storage of seal impressions and casts. The following report details the contributions from the speakers.

Provenance and Season of Production of Beeswax

Beeswax was mainly used for the production of wax candles, as wax candles produced less fatty smoke than candles made of animal fat. During the burning of the candles the beeswax burnt up. Only a small part of the beeswax was saved up in seals and an even smaller part in pieces of art. The provenance of beeswax can be established by searching for and identifying of pollen grains. If these grains are identified as produced by heath plants (Calluna vulgaris) one may conclude that the beehive stood on or near a field of flowering heath plants. However, for The Netherlands holds that in the 17th-18th centuries much beeswax was imported from Baltic countries. Would it be possible to identify the region and the time of the year of the beeswax production?

This question was positively answered by Carol A. Furness (The extraction and identification of pollen grains from a beeswax statue. Grana 33 (1994): 49-52), who investigated the pollen grains in a waxen statue attributed to Michelangelo (1475-1564). Carol Furness found pollen grains of plants growing in the coastal areas of the Mediterranean. Maybe Michelangelo obtained wax produced in the neighbourhood his Italian studio. So, on the basis of the pollen grains in the beeswax it is possible to locate the region of wax production and the period of the year of collecting. I am searching for similar papers as the one by Carol Furness reporting the provenance of wax for wax seals impressed in the 16th-17th centuries. The investigation of seals by tomography, a method borrowed from medical research, is known to me.

Anton C. Zeven, NL-Wassenaar August 2016.

Les Sciences à l’heure médiévale

A podcast from Les Rendez-vous de l’histoire featuring Agnes Prevost discussing methods of scientific investigation and conservation of historical documents and seals.

Une plongée dans les sciences utilisées pour mener des investigations et faire ressurgir les secrets du passé contenus dans des objets médiévaux : étude des processus d’oxydation et de corrosion, analyse des encres, recherche des ADN sur des poils ou des cheveux.

Listen to the podcast.

Deterioration of white wax seals

The question posed by P. R. Eley was – “From the experience of conserving many hundreds of wax seals, why do uncoloured medieval seals appear less stable than those seals that are coloured? Rarely have I come across a good intact uncoloured seal, they tend to be unstable and rather crumbly and need much care in handling, whereas virtually all the coloured seals are robust and remarkably intact.”

Read our members’ replies here: